Page Contents

Writing Titles and Abstracts

Before you submit your research article for publication, you’ll need to create a title and an abstract. The following sections will help you create an effective title that helps readers find your work and write a strong abstract that summarizes your key findings.

Creating an Effective Title

When you’re writing a research article, your title might feel like an afterthought. You’ve invested so much time writing the manuscript – does the short title really matter that much? It does matter, in terms of your research impact. Indexing and abstracting services use titles to organize information online, so having a strong title increases your chances that interested readers will find your paper.

Here are five steps that you can take to create a title for your scientific research article.

Step One

What words would someone use to search for your article online? These words should appear in your title.

Step Two

One option for structuring your title is to use a three-part formula that includes

(1) your independent variable

(2) your dependent variable

(3) the object of your study.

Let’s take a look at an example title: The Effect of Temperature on the Population Growth of Honeybees (Apis mellifera). This title includes the three-part formula – the independent variable, the dependent variable, and the object of study.

The independent variable is the temperature. Temperature is the environmental factor that the study manipulated.

The dependent variable is the population growth. Population growth is the parameter that the study measured.

The object of the study is a specific organism – the honeybee, or Apis mellifera.

The title succinctly tells us these three key pieces of information. Not all titles will have all three components, but including them can be helpful for readers who are searching for your article.

Step Three

Let’s take a look at a vague title and consider what we can do to make it more specific.

A draft title is Habits of Elephants. The first step we can take to make it more specific is to think about what we mean by habits. There are many different types of habits or behaviours. Let’s say this study focused specifically on social bonding.

Secondly, we can think about the species. The title indicates that we’re looking at elephants, but we can be more specific. What type of elephants are we looking at? Are we looking at female or male elephants? Are we looking at adult elephants or developing elephants? As writers, we should be specific. Let’s say we’re looking at adult male African Forest Elephants.

Here’s the revised version of this title: Social Bonding Behaviour in Adult Male African Forest Elephants. Now we have a better sense of what type of behaviour the researcher studied and what population they focused on.

Step Four

You should aim for a specific and comprehensive title, but you don’t want your title to be longer than it needs to be.

The title “A Study of the Creation of Social Bonds by African Forest Elephants in Order to Form Alliances Against Aggressors” is wordy, so let’s consider how to shorten it without taking out the key information needed for indexing and abstracting. Let’s look at three things we can do to shorten the title:

a) We can first remove redundant phrases such as “observations on,” “a report on,” and “a study of” because the reader can infer this information. In our example title, we can remove the phrase “a study of.”

b) We can then identify and remove any nominalizations. Nominalizations are nouns or adjectives that are created from verbs. For example, the noun “creation” comes from the verb “create.” In the above title, let’s use “create” instead and start our title with the subject that performs this verb – African Forest elephants. So far, we have “African Forest Elephants Create.”

c) Next, we can identify and remove any wordy phrases. The expression “in order to” can be replaced with “to” to keep this title short.

Our new title is “African Forest Elephants Create Social Bonds to Form Alliances Against Aggressors.”

Step Five

Consider your phrasing. As a writer, you have flexibility here. You can choose to phrase your title as a statement of what your research was about, or you can phrase your title as a question, or you can phrase your title as a statement of your findings. If you’re not sure which option you prefer, check out your target journal to see examples of titles.

When other scientists are searching for articles to review the research in their field, the first thing they’ll notice about each one is the title. Taking time to carefully consider your title will ensure that other scientists who are conducting similar research can find your work and learn from it.

For additional instructions and examples of original and revised titles of scientific articles, see Victoria E. McMillan’s Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences (2016).

Reflection Activity

Composing a Written Abstract

The abstract is a critical part of your research article. Angelika Hofmann, author of Scientific Writing and Communication: Papers, Proposals, and Presentations (2017), explains that “knowing how to write an abstract is one of the most important skills in science, as virtually all of a scientist’s work will be judged first (and often last) based on the Abstract” (p. 325). As you probably know from your own reading experience, readers often judge whether or not to read a full paper based on the contents of the abstract.

Overall, the abstract should serve as a standalone summary that communicates your main points to readers so that they know whether or not they should read the paper, given their own research interests. Because the abstract is a summary, a useful strategy is to write it after you’ve completed your article. However, sometimes writers like to put together an abstract first to give them some direction. If you use this strategy, you may need to revise your abstract after you’ve written the full article to make sure that it still captures what you’ve said.

You’ll want to provide an overview of your article.

Spoilers are expected – in other words, you should reveal the answer to your research question in your abstract instead of letting the answer come as a surprise at the end of your article. You want the reader of the abstract to know what you found and why it matters.

Use the same structure of your article – Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion – as an organizing framework for your abstract.

Sometimes, you may be tasked with writing a structured abstract, in which you’ll use headings to showcase these sections. However, even if you’re not writing a structured abstract, following these categories is a good practice.

The abstract should include information that is in the article.

Don’t use your abstract to squeeze in information that you couldn’t fit in the article itself. In other words, don’t try to use the abstract as an introduction so that you can skip over some context in the Introduction to the paper.

Typically, an abstract will not include any references to other researchers or to tables and figures.

References, tables, and figures will be in the article itself.

Structuring Your Abstract

Start with a brief background statement, state your purpose or objective (and hypothesis if you have one), and then briefly describe the important points of your Methods.

Next, you can summarize your main results and indicate from your Discussion what the main answer to your research question is. Briefly state what your findings mean, and then indicate how these findings contribute to the research field.

Make sure that you don’t leave your results and your contribution out of the abstract. Because the abstract has such a short word limit, sometimes writers will get as far as the Methods and then run out of space for the rest of the story. Writing in this way leaves your summary incomplete. If you run out of words before you get to your results, keep writing until the end, and then look for ways to trim excess words and phrases so that you have room for the full story.

The following fictional abstract follows the structure described above.

The beekeeping industry has developed many treatments to reduce the presence of varroa mites (Varroa destructor) in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies, including behavioural modifications, mechanical adjustments, synthetic chemical treatments, and natural chemical treatments. However, limited research has investigated the effectiveness of natural chemical treatments. The purpose of this study was to determine which natural chemical treatment strategies are most effective for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies. We tracked the efficacy of natural chemical treatments across 20 honeybee colonies in Guelph, Ontario. Our treatment types included essential oil (thyme), sucrocide spray, oxalic acid trickling, and formic acid strips. Formic acid treatment was the most effective treatment for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies. This finding suggests that this treatment is an effective option for Ontario beekeepers to control mite infestations.

You can use this structure as a starting place for your own abstract.

This abstract starts with a succinct description of the background to this research.

- In sentences one and two, we learn about the different ways that the beekeeping industry treats honeybee hives for varroa mites, and we also learn what the research has not yet explored.

- Next, in sentence three, we learn the question guiding this research, which is phrased as a purpose statement.

- In sentences four and five, the researcher briefly summarizes how they answered their question.

- In sentence six, the researcher states the main results.

- Finally, in the last sentence, we learn why these results are important and how they apply to the industry.

This succinct summary of the research findings allows other honeybee researchers to determine the relevance of this study to their own work.

Reflection Activity

Graphical Abstracts

Nearly all journals require a traditional, or text, abstract along with your research article. Some journals, however, may also publish other kinds of abstracts, including graphical and video abstracts. These abstracts are designed to supplement, rather than to replace, the traditional abstract. Check the guidelines of your target journal to find out whether you will need to create one of these types of abstracts for your research article.

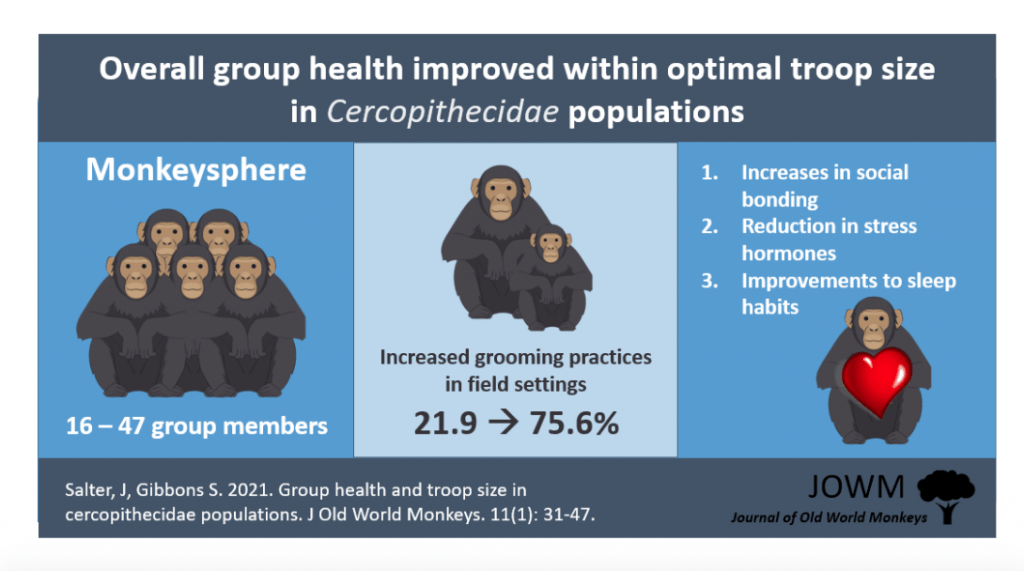

A graphical abstract is a single image that represents the major findings of a research article. Graphical abstracts summarize the major findings of a research article using a visual format, which allows readers to distill information quickly. Two common types are diagram style and visual style.

Graphical abstracts in the form of diagrams are particularly common within the field of chemistry and are often used to showcase a chemical structure or reaction. Journals that feature graphical abstracts of this style will instruct authors to create them and submit them with their manuscripts. See, for example, the submission guidelines from Nature Chemistry.

Graphical abstracts with a visual style that feature illustrations and background context are particularly common within the medical sciences. Andrew M. Ibrahim, who served as the creative director for the journal Annals of Surgery, introduced the visual abstract format for social media in 2016. Academic journals will share visual abstracts on Twitter and other platforms to draw attention to the research they publish using the hashtag #VisualAbstract. While some journals require that authors submit their own visual abstracts, other journals employ designers that will create abstracts for authors. See Ibrahim’s website for a primer on how to create a visual abstract.

Visual Abstract Example

Visual abstracts present findings in a clear, easy-to-digest way and so help readers decide whether to read an article in full.

Visual abstracts are designed to supplement, rather than to replace, traditional text abstracts. As Andrew M. Ibrahim notes, a visual abstract serves as a trailer for a research article that you can share on social media using #VisualAbstract.

NOTE: For educational purposes, we’ve created fictional visual abstracts for fictional scientific research articles. The fictional examples are intended to illustrate writing techniques and are not designed to teach scientific content. Please note that the scientific content and data on this page is fictional.

The following fictional abstract was developed in the visual style introduced by Andrew M. Ibrahim, former creative director of the journal Annals of Surgery.

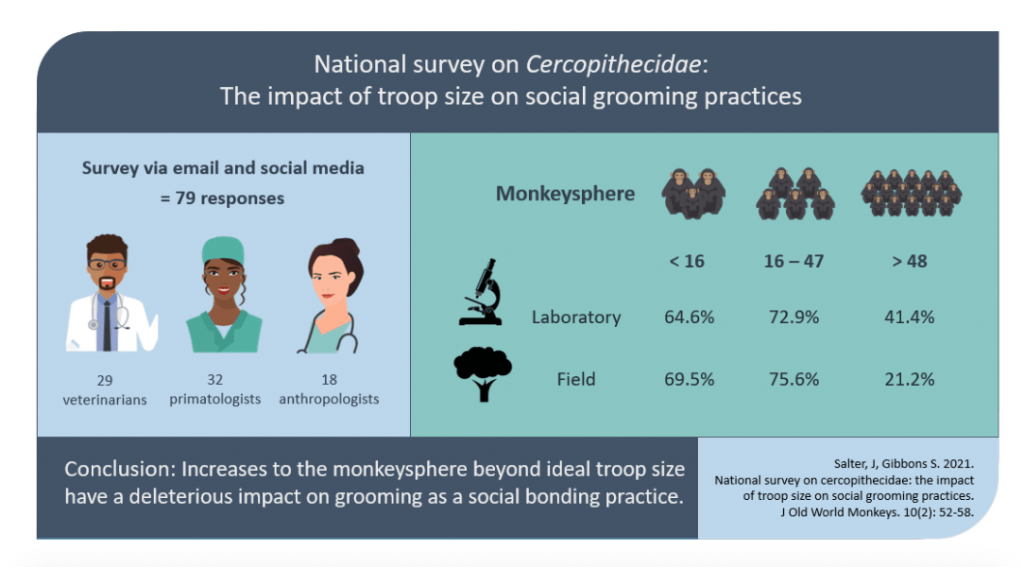

This abstract has three key components: the title, visuals, and the citation.

The Title

The title of a visual abstract summarizes the research question or the major finding.

The title of the above example of a visual abstract is “National survey on Cercopithecidae: The Impact of troop size on social grooming practices.” From this title, we can infer that the research question this article explores is how the troop size of these monkeys impacts their social grooming practices.

The Visuals

The visuals in a visual abstract will summarize important outcomes, highlight significant data, and show comparisons.

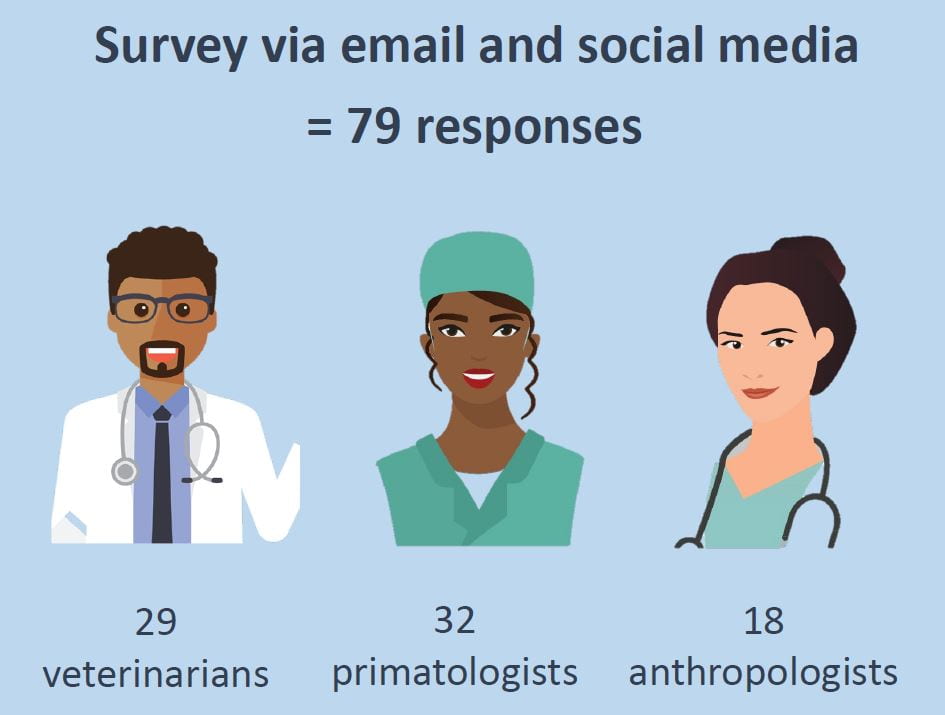

Although an article may have many findings, a visual abstract will present one to three main findings in a visual format. These visuals provide a preview of the major findings of the article for readers. This abstract includes two main visuals: one on the left which indicates the methods used and one on the right which summarizes the findings.

The visual on the right includes illustrations of the 3 authorities consulted for this research: veterinarians, primatologists, and anthropologists. The text above the visual informs us that these experts were sent a survey via email and social media and that 79 responses were collected. Below the images, we see how many of each expert contributed to the total response numbers.

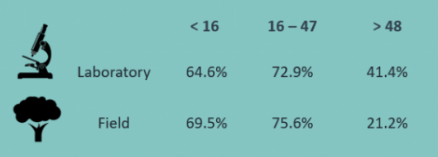

The visual on the right includes illustrations of three monkey troop sizes: small, medium, and large. Below the visual, the text indicates the quantitative composition of these three troop sizes. Small consisted of less than 16 monkeys, medium was 16 to 47 monkeys, and large was more than 47 monkeys.

In this section of the abstract, we also have images that represent the laboratory and the field settings – the two places where experts observed the social grooming practices of monkeys. We also see the major data collected by this study: the percentage of monkeys for each troop size that engaged in grooming practices in the lab and in the field.

By quickly comparing these numbers, readers can learn that social grooming practices were highest for the monkeys in the medium troop size. They can also learn that small and medium troops engaged in more social grooming practices in the field, whereas large troops engaged in more social grooming practices while in the laboratory setting. However, if a reader does not look closely at these numbers, they can still see the conclusion highlighted below in both visuals: increases to the monkeysphere beyond ideal troop size have a deleterious impact on grooming as a social bonding practice. These visuals, which show the major finding of this article, can be shared on social media to draw attention to this research.

The Citation

Finally, a visual abstract should provide a citation that indicates who the authors are and where the research was published. This information helps readers who encounter the visual abstract on social media know where they can go to read the full article.

Reflection Activity

Conclusion

Now that you’ve learned and practiced techniques for writing a title and an abstract, you’re ready to think about revising your research article before submission and responding to feedback from peer reviewers.

The content of this page was created by Dr. Jodie Salter and Dr. Sarah Gibbons.