Page Contents

Writing the Introduction

The Introduction to a research article answers, “What is your research question, and why did you investigate it?”

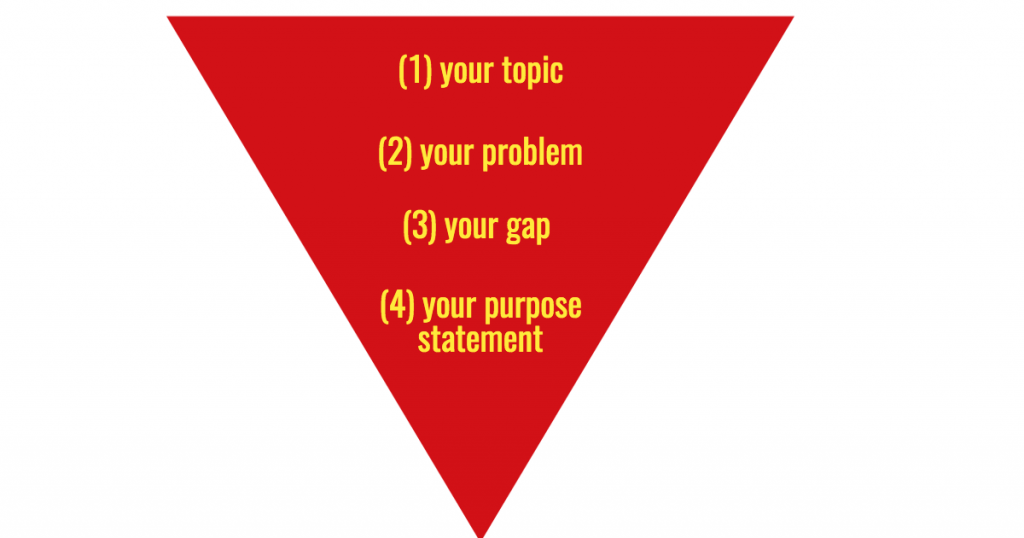

The four main components of the Introduction are (1) your topic, (2) your problem, (3) your gap, and (4) your purpose statement.

These four components help you tell the story of your research. You can picture your introduction as a funnel that starts with your broad research topic and then narrows in shape as you progress toward your specific purpose statement.

Topic

Describe your topic and provide sufficient background information to give the reader context for your work. Keep in mind that you won’t be able to include everything. As you’re deciding what to include, think about what key information your reader needs in order to understand your research.

Problem

Describe the problem that your research explores. Research topics are associated with issues that deserve attention.

For example, research problems can be related to environment, design, or health. Telling your reader about the research problem helps them understand why your research is important and what’s at stake.

In your description of the problem, reference research that shows how others have attempted to address this problem. Rather than providing a full literature review, provide key pieces of information that situate your own research.

Gap

Describe the knowledge gap that your research addresses. The gap refers to aspects of your problem that other researchers have yet to investigate. This gap provides justification for your own research project. You may be addressing the same problem as other researchers.

However, part of articulating your gap is showing how you are approaching the problem from a different angle or perspective that hasn’t been explored in the science community, or using an innovative method.

Perhaps research on your topic to date has focused on effects, whereas your research focuses on causes. Maybe research on your topic has not explored the full scope of the problem, so you investigated whether this problem affects other processes, mechanisms, populations, species, or tissues.

Purpose Statement

Describe the purpose of your study. Your purpose statement tells your reader what research question you investigated. Make sure that you write your purpose as a statement rather than as a question. Your purpose should be specific so that readers have a clear picture of what you did in your study.

Image Credit: Disability:IN

Four Key Components of the Introduction Section – An Example

The following video provides an example of the four key components of the Introduction section. When you are writing or revising this section of your scientific research article, be sure to explicitly include the broad topic, the gap, the problem, and the purpose statement.

NOTE: For educational purposes, we’ve created fictional excerpts that resemble passages from scientific research articles. The fictional examples are intended to illustrate writing techniques and are not designed to teach scientific content. Please note that the scientific content and data in this video is fictional.

[Background sounds of bees buzzing and birds chirping]

There are four key components in the introduction section of a scientific research article. [The first page of a published scientific article showing key sections: title, article info, abstract, and introduction. The Introduction section zooms into full screen view.]

Let’s imagine that a researcher is writing an article about varroa mites in honeybee colonies. This writer would start their introduction section by letting the reader know that the varroa mite is a parasite that feeds on honeybees. This is the BROAD TOPIC of this research article.

Then, the writer explains that varroa mite infestations weaken honeybee hives and contribute to their collapse. These infestations limit the ability of beekeepers to produce honey. This specific information about varroa mites highlights the PROBLEM that this research will explore, which is the second key component of the introduction. By outlining the problem in this way, the reader immediately knows why they should care about varroa mites and varroa mite infestations.

Next, the writer will then outline how other researchers have attempted to address this problem. For example, some researchers have looked at efficacy of mechanical adjustments to colonies as one way to reduce varroa mite populations. Other studies have explored the use of synthetic chemical treatments to reduce these mite populations.

Our writer will then indicate the RESEARCH GAP in research by telling the reader what hasn’t been done. [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] The writer explains to the reader that “The beekeeping industry has developed many treatments to reduce the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies, including behavioural modifications, mechanical adjustments, synthetic chemical treatments, and natural chemical treatments. However, limited research has investigated the effectiveness of natural chemical treatments.” This last sentence highlights the gap in research, which is the third key component in the introduction section.

The writer will then indicate the fourth key component, which is the PURPOSE of their study. [A laptop displays the following voiceover text on screen.] When writing about the purpose, the writer shifts the language of their research question: “What natural chemical treatments strategies are most effective for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies?” They shift the language of their research question from a (Research) question into a (Purpose) statement. In this varroa mite article, they would include the sentence “The purpose was to determine which natural chemical treatment strategies are most effective for reducing the presence of varroa mites in honeybee colonies.”

So, when you are writing or revising the introduction section of a scientific research article, be sure to explicitly include these four key components: the broad topic, the problem, the gap, and the purpose statement.

Hypotheses and Objectives

Some articles within the sciences will include a hypothesis and a prediction as part of the Introduction. However, in many disciplines within the sciences, a purpose statement is enough.

Whether you include a hypothesis in your research article depends on what type of research you’re doing, so get to know whether hypotheses are common in your field.

Should I include a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a potential answer to your research question. If your research tested a hypothesis, then you would include your hypothesis as part of your Introduction.

No, if you didn’t propose an answer to your question as part of your research process because your project was more descriptive or exploratory, you wouldn’t include a hypothesis in your research article.

Some writers will also include specific objectives. If you’re including objectives, you will still need to include your purpose statement and your hypothesis, if you have one. Without knowing your overall purpose, readers may not understand why you’re trying to achieve your specific objectives. When you’re writing your purpose statement or your hypothesis, make sure you use strong verbs that clearly show the relationship between variables.

In Writing Science: How to Write Papers That Get Cited and Proposals That Get Funded (2012), Joshua Schimel provides a list of “fuzzy” verbs that are likely to confuse your readers. Some examples are affect, conduct, facilitate, implement, occur, and perform. In contrast, strong verbs that show clear relationships include accelerate, create, decrease, disrupt, increase, inhibit, invade, mitigate, modify, and react (Schimel 2012, p. 139).

Writing Tips

Below are five writing tips for writing your Introduction section:

Tip One – Move from Broad to Specific

Your Introduction should start with your broad research topic and then narrow in focus as you progress toward your specific purpose statement. In your Introduction, you’ll need to summarize background research to situate your study. Once you’ve decided on the research that you plan to include, consider which studies are furthest from your own work and which ones are most similar. A helpful approach when writing is to start with the broad studies before discussing those specific studies that your own work builds upon. Moving from what’s broad to what’s specific creates a logical flow and helps you guide your reader toward your purpose statement.

Tip Two – Move from Known to New

Known to new is a useful technique that helps you create strong connections between your sentences that will make your writing more cohesive. You can create clear connections between sentences by ending a sentence with a specific word or phrase and then using this word or phrase at the beginning of the next sentence. Doing so creates a strong verbal bridge for your reader to follow along as you introduce new concepts.

Start your sentence with information that is known to the reader and conclude it with new information that you want to introduce.

Let’s take a look at two example passages:

- Honeybee colonies can collapse due to many factors. Varroa mite infestations are one factor.

- Honeybee colonies can collapse due to many factors. One of these factors is varroa mite infestations.

The first passage does not follow the known to new technique. In particular, the second sentence starts with new information – varroa mite infestations – instead of building on the information the reader has already been given. A reader who is unfamiliar with this topic may find this sentence jarring because they thought the writer was discussing honeybee colonies, and now they are starting to discuss what appears to be a new topic: varroa mite infestations.

The second passage follows the known to new technique. The writer tells us that honeybee colonies can collapse due to many factors, and then shares that one of these factors is varroa mite infestations. Using “factors” at the end of the first sentence and again at the beginning of the second sentence helps the reader understand the relationship between honeybee colonies and varroa mite infestations.

Although both of these passages contain the same content, and the reader will eventually receive the same information, the second one is easier for readers to follow because it uses the known to new technique. Known to new is particularly helpful for readers who are unfamiliar with your research topic, but even scientists who are familiar with your topic will prefer reading sentences that follow the known to new technique because this technique creates a smoother reading experience.

Keep in mind that known to new is one technique for creating cohesion. Another technique is using transition words like “however” or “furthermore” in between sentences to show the relationship between ideas. Although transition words are helpful, starting every sentence with a transition word can feel repetitive, so known to new is a valuable technique that you can make use of as a writer.

Tip Three – Use Active Voice

Use active voice instead of passive voice as much as possible. Active voice refers to the order of words within a sentence. An active sentence features a traditional subject-verb-object order. In other words, the sentence starts with the subject or agent, then includes the verb or action, and then includes the recipient of the action.

A simple example would be “Oncologists study cancer.” Oncologists are the subject of the sentence, study is the verb, and cancer is the object.

A passive voice sentence places the agent who performs the action at the end of the sentence or omits the agent entirely. Two examples of passive sentences are “Cancer is studied by oncologists” and “Cancer is studied.”

Writing experts recommend active voice for three reasons:

- The first is that we tend to speak in active voice, so this structure feels more natural for many readers.

- The second is that active voice is more concise, which matters when you are writing more complex sentences.

- The third is that active voice forces you to be more precise because you need to declare who or what performs an action. While passive voice allows you to say “Cancer is studied,” this sentence leaves the question of who studies this disease unanswered. Active voice forces you to answer who studies the disease.

However, although writing experts prefer active voice, passive voice is not grammatically incorrect, and it has its purposes too.

In some disciplines within the sciences, writers tend to use passive voice for certain sections of research articles, such as the Methods and the Results, in order to avoid using personal pronouns. For example, they might write “the temperature was measured hourly” instead of “we measured the temperature hourly.” Some writers prefer using passive voice in the Methods section to emphasize the procedure as opposed to emphasizing the researcher carrying out the procedure. When you’re looking at your target journal, pay attention to whether writers use passive voice in certain sections of the research article to avoid using personal pronouns.

Tip Four – Write Topic Sentences

When writing paragraphs for your Introduction section, ensure that each paragraph has a clear topic sentence that starts the paragraph and indicates what the paragraph will be about. Readers use topic sentences to navigate through a document, so constructing effective topic sentences will help them follow your ideas.

Tip Five – Write Concluding Sentences

When writing paragraphs for your Introduction section, ensure that each paragraph has a concluding sentence. This sentence should be distinct from the topic sentence. In other words, don’t use your concluding sentence to repeat what the paragraph is about. Instead, write a sentence that describes the significance or implications of the material that you’ve covered. Don’t assume that your reader will draw the same conclusions that you will from the sources that you’ve described. In your concluding sentence, let the reader know what they should take away from this research, and then transition to your next topic.

Review Exercise

Compare the following two paragraphs from a fictional research article.

Paragraph One

The number of invasive Varroa destructors in an Apis millefera colony can be reduced using behavioural modifications, mechanical adjustments, synthetic chemical treatments, and natural chemical treatments. Buzzz et. al (2021) have investigated the efficacy of natural chemical treatments. They found that formic acid treatment was more effective for reducing mite populations than sucrocide spray treatment. The purpose of this study was to investigate the efficacy of natural chemical treatments.

Paragraph Two

The varroa mite (Varroa destructor) is a parasite that has had a devastating impact on western honeybee (Apis mellifera) populations. Varroa mites feed on honeybee body fluids and spread a variety of pathogens, including a disease called varroosis. Because these mites can reproduce only in the environment of a honeybee colony, colony infestations are very common. These infestations weaken honeybee colonies, contribute to colony collapse, and limit the ability of beekeepers to produce honey. Researchers have shown that the varroa mite is the greatest threat to honeybee populations in Ontario (Singh et. al 2018; Chen et. al 2019; Buzzz et. al 2020). In order to manage varroa mite infestations, Ontario beekeepers must regularly monitor and treat their colonies.

Most readers will prefer paragraph two. As Angelica Hofmann notes in Scientific Writing and Communication: Papers, Proposals, and Presentations (2017), the opening paragraph of an Introduction should introduce the broad topic under investigation and why it matters (p. 245). The first paragraph may be confusing for readers because the writer introduces potential solutions for the problem of varroa mite infestations before introducing the reader to the topic under investigation and the research problem. In contrast, the second paragraph introduces the topic and problem so that the reader knows what’s at stake in this research.

Conclusion

Now that you’ve identified four key components of the Introduction, you can return to your research article map (see “Getting Started”), and identify your own topic, problem, gap, and purpose statement. Once you’ve articulated these four components, you can start to outline your draft. Proceed to the next section on writing your Methods.

The content of this page was created by Dr. Jodie Salter and Dr. Sarah Gibbons.